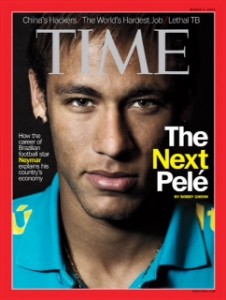

Revista Time

02/2013

Por Bobby Ghosh e Andrew Downie

Why Is Soccer Superstar Neymar Still Playing in Brazil?

As the spiky-haired young man hailed by all of Brazil as the Next Pelé places the ball on the penalty spot, I sit rigid with anticipation on a field-level seat barely 10 m behind the goal. Moments later, the blurry orb comes straight at me with explosive speed, freezing me in fear. In the instant before the ball catches the net I know the utter hopelessness a goalkeeper must feel when Neymar da Silva Santos Jr. bears down on him. Then the stadium erupts, and all eyes follow the superstar as he wheels away in jubilant celebration, followed by a whooping pack of teammates.

It’s the last game of the 2012 league season at the history-laden Vila Belmiro Stadium in Santos, the coastal municipality in southern Brazil that gave the world O Rei do Futebol, or King of Soccer, as Pelé is known. And it is entirely apt that the current claimant to his crown should play for his club, Santos FC, and on his happy hunting grounds. If it weren’t for poor health, the great man himself would be watching from his box seat as Neymar — in the best Brazilian tradition, he goes by a single name — notches two goals and one assist in Santos’ 3-1 trashing of Palmeiras.

The win was, at best, a small consolation for Santos fans. One of Brazil’s most successful club teams ended the season a disappointing eighth in the Campeonato Brasileiro, or Brazilian Championship; its only serious silverware of the year was the state championship of São Paulo. This was a huge comedown from the 2011 season, when a Neymar-inspired Santos won the Copa Libertadores, South America’s equivalent of the Champions League.

But as they streamed out of the Vila Belmiro under the watchful gaze of riot police, the fans were in an exultant mood. “We won the most important thing of all,” said Jele, a young graphic artist who also goes by a single name. He pointed to a giant poster of Neymar that looms over a bronze bust of Pelé. “He is staying. And as long as we have him, we can win everything.”

That Brazil’s most precious athletic asset isn’t being sold off to a superrich European team says less about the team’s loyalty to its fans than it does about Brazil’s power as a rising economy. Despite flat growth last year, Brazil’s past decade of economic expansion, about 4% annually, and increasing national wealth has shown up in many places, from aircraft and auto manufacturing to information technology and its huge agricultural sector. Rich Brazilians have reinflated Miami’s busted real estate market. At home, poverty is shrinking. Unemployment, a record-low 5.5%, has been falling as wealth is being spread.

It’s not that Brazil lacks problems: crime rates remain high, vast slums scar the urban landscape, poor infrastructure makes for epic traffic jams and hurts business. But issues like corruption that retard developing nations are finally being addressed with muscular investigations and trials, and a booming private sector is producing world-class businesses.

That progress is nowhere more evident than in Brazil’s professional soccer league. It’s no surprise that a country famously overabundant with superb players should export its surplus — some 1,500 a year leave for foreign leagues — but in recent years, there’s been a spike in the number of returning players: more than 1,100 went home in 2012, up from 974 in 2008. Brazil’s trade deficit in footballers narrowed to 315 last year from 556 in 2008. In large part, this is because the Brazilian league, just like its economy, has become more sophisticated and profitable. Not surprisingly, struggling Argentina, Brazil’s great rival, is the world’s leading exporter of soccer talent — its brightest star, four-time Ballon d’Or winner Lionel Messi, plays in Spain.

Neymar is a Messi-class talent. He’s a player whose ability to change speed and direction is augmented by astonishing ball skills. There’s an unaffected effervescence to his game, a refreshing change from the calculated efficiency of European soccer that has infected the Latin American leagues since the 1980s. In an era of pass-and-move, Neymar is not afraid to keep the ball, dribble and weave past his opponents rather than simply figure out the most effective way of moving it forward. It’s too early to say if he’s as good as Pelé, but he certainly plays with the King’s sense of sheer joy. “He plays like Brazilians used to, without cynicism,” says Juca Kfouri, the country’s pre-eminent soccer commentator. “He plays with a wink and a smile, like he’s having fun.”

In 2012, his most prolific year yet, Neymar scored 52 goals in 58 games, including nine in 11 for the Brazilian national team. Those stats didn’t escape the attention of European soccer powerhouses like Barcelona and Real Madrid, which head a long queue of clubs seeking to take Neymar away from Brazil.

Neymar has politely turned down all advances. This is highly unusual for a player of his talent and age: he turned 21 on Feb. 5. He could easily be making tens of millions of dollars at Real Madrid or Manchester United. But he insists he’s not going anywhere, at least until 2014, when his current contract with Santos expires. Neymar tells me he’s perfectly content to remain in his working-class hometown on the Atlantic Coast. “I always do what my heart tells me,” he says. “For me, the right time has not come to leave Brazil. I am very happy.” For his part, Santos’ president, Luis Álvaro de Oliveira Ribeiro, says he defines his job as “making sure Neymar has no reason to go.” That means paying his star a world-class wage, allowing him to make separate deals with sponsors and giving him time off for his endorsement commitments. None of this would be possible without Brazil’s economic success.

To São Paulo economist Ricardo C. Amorim, Neymar symbolizes the newfound ability of emerging economies to fight the brain drain, usually to the West, of their best and brightest. A strong Indian economy, he points out, is better able to retain its best engineers from heading to the U.S. and even lure some back. Brazil’s gravitational pull is likewise growing stronger. In the past decade, more than 30 million people rose from poverty into what Brazilian economists call Class C, defined as those with a monthly income of $140 to $500. That’s 30 million more people who can now afford to pay more for soccer tickets, buy club merchandise, watch games on cable, buy Adidas cleats and Nike shirts.

There’s Gold in the Goals

As a result, the combined revenues of Brazil’s top 100 club teams grew from $396 million in 2003 to $1.4 billion in 2011, according to research compiled by sports consultant Amir Somoggi; revenues for 2012 are expected to top $1.35 billion. The top 10 teams account for 65% of the pie, giving them a windfall not unlike the country’s discovery of huge offshore oil reserves. Santos’ revenue soared 548% to $105.2 million between 2003 and 2012; at Corinthians, the league’s top earner, it grew 481% to $157.3 million. Much of this growth is due to better TV deals, new sponsors and merchandising.

For too long soccer was a cesspool of corruption in Brazil. The teams, technically not-for-profit organizations, borrowed huge, had notoriously opaque bookkeeping and sold players to stay solvent. Unscrupulous agents also peddled Brazil’s soccer players like they would its cattle, shipping them to all corners of the world — and letting them fend for themselves if things didn’t work out. The former head of its football federation, Ricardo Teixeira, stepped down last year amid allegations that he and his predecessor (and father-in-law) João Havelange received millions of dollars in bribes for World Cup marketing rights.

It’s hard to imagine now that the Brazilian government in 1961 had to declare Pelé a national treasure to prevent European clubs from absconding with him in his prime. The Next Pelé needs no legislation to hold him: he can earn European wages without leaving home. France Football magazine listed Neymar as the 13th-highest-paid player in 2012, with annual earnings of $18.26 million. About half came from endorsements and commercial deals. Although the total trailed Messi’s $44 million, it still made Neymar the second-highest-paid Brazilian: Kaká, playing occasionally (and unhappily) for Real Madrid, made $20.5 million. And at 30, Kaká’s best years are likely behind him.

Neymar insists his income has no bearing on his druthers to remain at Santos, saying: “I think my decision would have been the same 15 years

ago.” But even assuming he’d have settled for a fraction of his current wage, it would not have been his call. If the club’s revenue was at the level of preboom Brazil — $19.19 million in 2003 — Ribeiro, the president, could hardly have resisted a $65 million offer for Neymar from, say, Chelsea.

Instead, Ribeiro can now dream of building on Santos’ newfound riches: he hopes to move the club out of the Vila Belmiro, a quaint, century-old stadium that can accommodate 17,000, to an arena three times its capacity on the outskirts of town. He also made an audacious bid to bring back one of Santos’ prodigal sons, Robinho, from AC Milan: that deal could be concluded in the middle of the year. “This is a great time for Brazilian football,” Ribeiro says. “It is reinvigorating its self-esteem by showing that we are no longer just exporters of players.”

The Prodigal’s Return

Until the economic boom, the traditional arc of a Brazilian superstar’s career ran thus: at 14, his talent was spotted by a local club; four years later, he was traded up to one of the smaller European leagues, like Portugal’s, where his prodigious performances marked him as the Next Pelé; he had a couple of good seasons before a superclub like Real Madrid, AC Milan or Manchester United came calling. At Neymar’s age, he was a full-blown global celebrity, with flashy cars, model girlfriends and big endorsement deals. If he had the right temperament — and durable knees — he could stay at the top of the European tree until his early 30s. Slowed by age, he then moved on to second-tier leagues, like Russia’s or Turkey’s, where he could still pull down a million-dollar salary; by 35, he was squeezing out the last few paydays playing in Qatar or Japan.

The pattern started to change in the late 2000s, when better-run, better-financed Brazilian clubs began to poach expatriate players in the Spanish and Italian leagues who might otherwise be heading east. In 2009, Corinthians snagged Ronaldo, star of the 1998 and 2002 World Cups, from AC Milan. To pay his salary, the club allowed advertising on its shirtsleeves for the first time — and gave Ronaldo the proceeds. “It was a risk, because we’d never sold that space before,” says Corinthians vice president Luis Paulo Rosenberg. “But the marketing rewards were worth it.”

Although slowed by multiple injuries and conspicuously overweight (some São Paulo restaurants named their fattiest steaks after him), Ronaldo was good value, scoring 29 goals in 52 league matches over two years. His star power was a boost for Corinthians at home and abroad. “People who had never heard of us, in Thailand and Vietnam … they knew us now because we had Ronaldo,” says Rosenberg. Corinthians’ fortunes have not looked back since: it won the Copa Libertadores in 2012, before beating Chelsea in the final of the Club World Cup in December.

Ronaldo’s remunerative return paved the way for other prodigals, among them Ronaldinho Gaúcho from Milan, Luís Fabiano from Seville, Fred from Lyon, Juninho Pernambucano from Qatar, Deco from Chelsea and Jô from Manchester City. Many were already past their prime, but not all. Alexandre Pato, who moved from Milan to Corinthians in December, is only 23 and one of the world’s top strikers.

They are going home to a new kind of football organization. “The infrastructure is much better than it used to be, the training grounds, the medical staff, the support staff,” says Deco, who left Brazil as a callow 19-year-old in 1997 to play first in Portugal (where he became a citizen, as have Brazilian players in other nations), then Spain and England before returning to lead Fluminense to the 2012 Brazilian Championship.

It helps that the clubs are now able to recruit professional administrators. Rio de Janeiro corporate lawyer Elena Landau, a former director of privatization at Brazil’s national development bank, recalls the struggle to hire business managers at her favorite club, Botafogo, in 2003. “We were calling friends who had retired from corporate jobs and pleading with them to come and help run the club,” she says. “Now, you can hire smart young people with sports-management degrees from university.”

As a result, clubs like Corinthians have developed sophisticated marketing and brand-management strategies, the better to capitalize on their giant fan base at home and tap markets abroad. “They’re thinking like European clubs now,” says Washington Olivetto, chairman of the advertising firm WMcCann and well-known Corinthians fan. “They’re beginning to understand how much their brand is worth.” Club vice president Rosenberg points to the club’s 115 franchise shops in Brazil as an innovation for Brazilian football and talks about a long-term strategy to develop the Corinthians brand in China. The club sent two coaches to Guangdong province, to help train coaches there, and took a Chinese player, Chen Zhizhao (promptly dubbed Zizao by Brazilian fans) to São Paulo. “The Chinese response has been fantastic,” Rosenberg says.

The Cup Runs Over

As if to crown Brazil’s economic and soccer growth, the World Cup is being staged there in 2014. The government is spending $3.5 billion to build 12 new stadiums and upgrade existing venues, and $13 billion on roads, airports and other infrastructure that Brazil needs to stay globally competitive. All this is accompanied by the usual angst over the host nation’s ability to finish everything on time. Corinthians’ new stadium in the Itaquera suburb of São Paulo will cost about $410 million and seat 48,000. It will include the world’s largest video screen, bigger than the one at the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium. There will also be shops and restaurants, amenities that are common in European arenas but rare in Brazil. The Cup spending will boost the Brazilian economy, which is projected to expand more than 3% this year after a mere 1% in 2012.

For Neymar, the approaching World Cup will bring a new kind of pressure. If Brazil is to win the tournament and exorcize the demons of 1950, when it lost the final game at the Maracanã before 173,000 spectators, much will depend on his play. It’s no extra burden on him, he says, but allows that expectations of the Seleção, the national team, will be sky-high. Brazil is always a favorite, but “this Cup is happening at home, so the pressure on the Seleção is doubled.”

If his goals reclaim the World Cup for Brazil, Neymar will have only one thing left to prove: that he can cut it in the week-in, week-out grind of a big European league, like Spain’s La Liga or England’s Premier League. Can he go toe-to-toe with a Messi or a Robin van Persie — or, in an even more delicious prospect for fans, play alongside one of them? After all, many a Next Pelé and New Maradona has been found wanting in the arenas of Manchester, Madrid and Milan.

Neymar seems ambivalent about playing with the big boys in Europe. He describes Messi as “an idol,” and is plainly in awe of the FC Barcelona star. “It is fantastic how he is able to be decisive, to change a game,” he says. Both Neymar’s father and Santos coach Muricy Ramalho have said Barca, as Messi’s club is known, would be the perfect place for Neymar to make European landfall.

Neymar insists he’s not thinking that far ahead, and cautions against the assumption that he will leave for European shores. “It depends on how I feel in my heart,” he says. “I could continue to work with Santos.”

When I mention this to Jele, the Santos fan, he lets out a cry of mock anguish. “I don’t want to dream that, because I don’t dare to think it will come true,” he says. “But Neymar forces me to dream it!”