12/2015

By Ricardo Amorim and EIC

No, you did not read wrong. GDP contracted 7.0% in annualized terms in the third quarter, the São Paulo stock exchange index is near a six-year low, the country faces a micro encephalitis epidemic, endless corruption scandals, a political crisis and I have the nerve to talk about good news?

First good news: 2015 is near its end. Now the best news: at least in the economy, 2016 may not be as bad as most people fear, and it is nearly certain that the following years will be better, maybe much better.

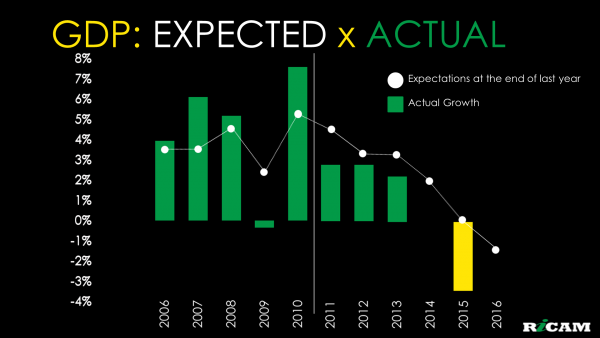

In order to understand why, we need to go a little back in time. President Dilma took office in 2011. There were two main trends since then. Year after year, growth expectations for the following year – measured as the average result of the survey carried out at the end of the year by the Central Bank among bank economists – deteriorated. Worse still, the actual growth in each year was worse than the expectations. In other words, the performance of the Brazilian economy is getting consistently worse since 2011.

Besides, since 2011 the Brazilian economy came second in terms of least growth in Latin America. Brazil is only second to Venezuela because their GDP will drop about 10% this year.

This was not always so: in the five previous years, trends were the opposite. At the exception of 2009 due to the impact of the global financial crisis, expectations showed a clear trend towards improvement and the actual growth of the GDP always exceeded expectations.

What changed in the Brazilian economic policy since 2011? A lot did. Perhaps the most significant changes were a strong increase in State interventionism and the government’s lack of courage to combat inflation.

A common trait in the economic policies adopted by Finance Minister Guido Mantega’s team during President Dilma’s first term in office was to try and solve problems based on the notion that reducing the remuneration of companies was part of the solution. The most striking example is possibly what happened in the electricity sector.

About four years ago the government diagnosed – correctly, by the way – that the Brazilian electric power was the most expensive among the 30 largest world economies. Something had to be done in order to reduce its cost. There were several causes to the problem. The most severe one was that the total taxes paid both by consumers and by electricity companies was the highest by far. Instead of drastically reducing taxes – which would require cuts in government expenditure – the government reduced taxes minutely and, as a condition to renew concessions for electricity utilities, demanded that they reduce their selling price to consumers. Prices fell slightly, to begin with. Since power consumption remained constant, the income of companies was reduced too. Unfortunately, the cost for companies is little flexible, since their main expense is to build infrastructure for power generation, transmission and distribution. What was the impact of the reduction, then, on power companies? Less revenue and constant cost slashed profitability and this led companies to cut investment, slowing down the expansion of power supply in the following years. To make things worse, Saint Peter does not seem to have liked the changes, and rain became scarce in part of the country, which matter a lot in a country where more than 50% of electricity comes from hydropower. Thus, four years on there is not enough power, for lack of investment, to offset demand at a lower level of supply, and prices had to be increased two- and even three-fold.

In short, economic policies encouraging consumption but discouraging production kept the confidence level of entrepreneurs in constant decline, reducing productive investment and generating two major imbalances in the Brazilian economy.

The first of them happened in the external accounts. The rise in cost to produce in Brazil made an increasing number of companies and consumers prefer to bring products from abroad rather than make or buy them here. When former Finance Minister Guido Mantega took office, 9 years ago, Brazil had US$ 10 billion annual surplus in the trade balance of manufactured goods. It exported US$ 10 billion more than we imported. When he left government 11 months ago it had a deficit of US$ 110 billion. This is why Brazil´s industry shrunk more than 20% since the launch of Programa Brasil Maior (Greater Brazil Program), which was created to supposedly stimulate competitiveness in the Brazilian industry, four and a half years ago.

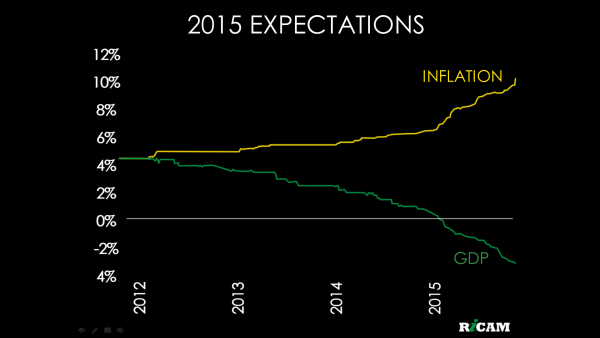

The second imbalance came from inflation. Increases in the cost of rent, labour and raw materials pumped inflation up and were not adequately combatted by the Central Bank, at least not until the election last October.

Worse still, the government held back, until the election, several prices it controls such as electric power, gasoline, bus fares, metro fares and other. After the election and with public accounts in shambles, increases came all at once – prices under government control went up 18% in average in the last 12 months – further exacerbating inflation.

Finally, the Dilma administration generated one more major macroeconomic disarray in public accounts. Increasing expenditure and a stagnant economy – with the ensuing decrease in tax collection – caused a growing fiscal imbalance that undermined confidence in the country, reducing investment and economic growth.

In short, the economic heritage left behind by the Dilma I administration to the Dilma II was a severely ill economy. In order to treat the economic cancer, exit Guido Mantega, enter Joaquin Levy and chemotherapy starts.

Economic policies change radically and – in fits and starts – they are curing the disease. The problem is that in the beginning the patient, the Brazilian economy, suffers both with disease not yet cured and the side effects of the economic chemotherapy itself. In other words, before Brazil´s economic imbalances are corrected, high interest rates, high dollar exchange rate and high taxes further depress the economy.

In order to adjust external accounts, the real (BRL) suffered a maxi devaluation which made foreign products more expensive, which makes the option of importing them less attractive and stimulates their production locally. As a consequence, the results of the trade balance start to improve.

However, the rise in the dollar exchange rate has a considerable side effect. Making imported products more expensive, it feeds inflation. So as to combat inflation, the Central Bank doubled the basic interest rate to 14,25% p.a., making credit to consumers much more expensive. With high interest rates, consumers cut back on purchases. With less demand for the goods they sell, businesses cannot increase their prices as much, which will end up reducing inflation.

Bullish pressure on inflation was such that high interest rates haven’t yet done the trick. On the contrary, inflation this year will be the highest in 13 years. Inflation should come down next year, but not enough to reach the center of the target – which is 4,5%. Besides, even the ceiling of the inflation target – which is 6,5% – is at risk to be exceeded, which may force the Central Bank to increase interest rates even more in the beginning of next year.

On the other hand, due to the deepest and longest recession in over 30 years, the drop in inflation should continue in 2017, creating conditions for interest rates to go down between the end of next year and the beginning of 2017. This would make credit and consumption grow again and would encourage productive investment and the generation of jobs.

For that to happen, Brazil must first sort out one last macroeconomic misfit generated in the first term of President Dilma in office – that of public accounts. Like in a family or a business, there are only two ways to bring government accounts under control: to raise taxes or to cut expenses. In fact, to cut expenses would be the ideal solution in a country where the total public expenditure is one of the highest among all emerging countries, and the quality of public services is squalid.

In the last year the government raised some taxes but this was not even enough to counter balance the fall in tax collection caused by the shrinking GDP. In summary, so as to straighten out public accounts, resume confidence, investments and growth, the government will need to further cut its expenses or increase taxes, which it has not been able do due to the political crisis.

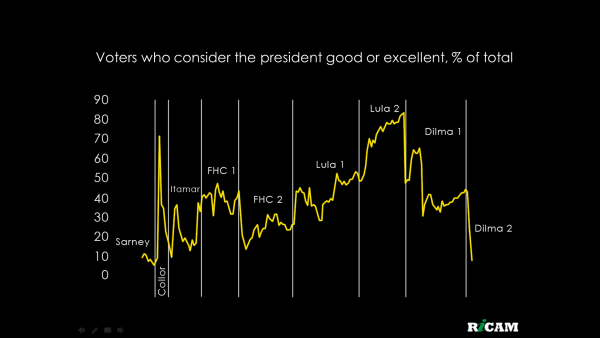

The President was re-elected thanks to a discourse in which the country was thriving, and inflation, external accounts and public accounts were no problem. After the election, economic imbalances and their negative impact on jobs and salaries became evident, spreading a feeling of fraud (which is being called “electoral larceny”). On top, generalized corruption accusations involving leaders of the Executive and of Congress further helped the President’s popularity to go down to one digit, amid troubled relations with the Legislative power, which started to block the projects required to recover public accounts.

This is where the game should change in 2016. As the political war and the huge fiscal deficit last, productive investment dries up and unemployment does not cease to increase – soon we shall attain a two digit unemployment rate, twice that of a year ago. In theory, this trend towards economic deterioration could remain unaltered for another three years, till the 2018 election. My impression, though, is that long before that – probably still in 2016 – the Brazilian socioeconomic fabric would be frayed to such a point that increasingly serious conflicts would emerge, making the now unstable political balance impossible to sustain. Two other possibilities seem more probable to me.

The first of them is a “pizza” solution as Brazilians call it. The Executive and the Legislative powers would come to some agreement ensuring the fiscal adjustment in exchange for some type of “immunity” for the people investigated in corruption scandals, both in the Executive and the Legislative, including members of government and of the opposition. The cost of missing the opportunity to put an end to the culture of accepting corruption would be immense for the country, in medium to long term. This culture would in fact be strengthened. In the short term, however, it would unleash the economy, allowing prospects of growth for coming years to improve, for the first time since 2011.

What makes the above “pizza” option less likely is that it would require the blessing of “the other side”. It would only be possible if the Judiciary is controlled or co-opted by the Executive Branch– and it has been rather insulated from political pressure so far.

We are left then with the second alternative: the current crisis lingers on, and is aggravated along the beginning of next year, with rising unemployment and an even greater fall in popularity and reduction in support of the President, making her stay in office impossible. Let us remember that former president Collor did not fall only on account of corruption charges, but because of his one digit popularity and of being gradually abandoned by his allies. In the current case, a new president – be it vice-president Michel Temer or as a result of a new election – would probably count on a more solid political basis, permitting the fiscal adjustment to be concluded, along with resuming confidence and growth.

Therefore, even though the timing, the pace of recovery and consequences in the medium and long term are so different, in both cases it is probable that some time in 2016 – or along 2017 at worst – the Brazilian economy will start on the path of recovery. It is even more probable that, once started, recovery will be more vigorous than what is now forecast by most economists and businesses.

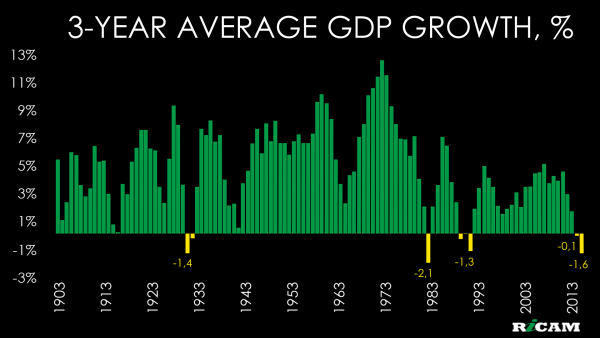

The Brazilian economic performance in the 2014-2016 span – the expected average contraction of the GDP being 1.6% p.a. – will be the second worst in the last 115 years. In all other cases of significant contraction of the GDP, it was followed by accelerated growth in the following years.

Almost no-one expects it to happen this time around. Quarterly projections by the majority of analysts point to a falling GDP until the first quarter of next year, followed by stagnation for nearly two years after that. Brazilian and international economic history suggests that the fall in the GDP in coming quarters may even be more intense, and last longer than analysts now project, but once the fiscal gap and the political crisis are resolved, and once confidence is resumed in the Brazilian economy, recovery, when it happens, will be much stronger than is foreseen today. Like in the period previous to the Dilma administration, for at least a few years economic surprises will be positive again and growth will speed up instead of slowing down, which should buy Brazil some time to tackle several much needed structural reforms in its economy.

I am not the only one who sees that long term economic expectations and consequently prices of assets in Brazil are far too pessimistic. To avail themselves of the business opportunities that such positive surprises will usher in, three foreign companies made billionaire investments in the country in the last week. In cosmetics, French Coty bought part of Hypermarcas. In communications, American Omnicom bought the ABC Group. In aviation, Chinese HNA bought Azul.

Are you, your investment and your company ready for the surprises that are on the way in Brazil?

Ricardo Amorim is a host in Manhattan Connection on Globonews, CEO of Ricam Consultoria, the most influential Brazilian on LinkedIn, the only Brazilian on the Speakers Corner list of best and most important world lecturers and Brazil’s most influential economist according to Forbes Magazine.

Follow him on Twitter: @ricamconsult