08/2019

By Ricardo Amorim

Economists usually communicate using jargon that is beyond the understanding of outsiders to their field. Add to that the average level of education, which leaves much to be desired, and the result is that the vast majority of people ignore how the economy works.

On the other hand, everyone knows very well where their own financial situation stands, whether it improved or got worse in the last years. It is based on the perception of one’s own financial comfort or unease that most voters decide who they vote for.

In elections for President, governors and mayors – when a single candidate is to be elected – there is like a referendum, based on each voter’s individual perception of being better off or not, and relating that to whoever is in power.

This understanding can be applied to the result of the primary elections in Argentina, which point to the probable victory of the Peronist ticket featuring Alberto Fernandez and Christina Kirchner over incumbent President Mauricio Macri in the October election. The worsening that this may bring about to the Argentinian crisis caused a 38% downfall in the Buenos Aires Stock Exchange index – the second largest drop in a single day in any stock exchange of the world since 1950, and a 24% devaluation on the peso. Both effects put together meant foreign investors had a 53% loss in a single day.

Why do Argentinians vote against Macri? The economic performance falls short of expectations and the financial situation of most Argentinians deteriorated. Macri was partially responsible for that. Had he been faster and more aggressive to liberalize the economy, allowing it to grow more in the long run, and had he adopted more aggressive short term measures of incentive, which might have entailed better economic performance in the last few years, and the poll result would have been different.

More important, however, than what Macri did or did not do were the conditions he inherited from his predecessor Christina Kirschner – only this is not understood by Argentinians. Imagine that you lend your house to a friend and he practically destroys it but fills the place with decorative items so you cannot see the destruction. Next, this friend leaves the house and another friend occupies your house for a while, fixes a few broken things, does not fix others. You then come back and find the house in visible chaos. You refuse to listen to the explanation of the second friend and send him out of the house.

This is precisely what Argentinians want to do to Macri. And since they do not understand that it was Christina Kirchner who handed the destroyed house to Macri, they are willing to lend it to her again, because they had the false sensation that the house was in better shape with her.

Why should it matter to us, Brazilians? First of all because the Argentinian economic crisis shall get worse and this will further reduce our exports to them, at the cost of tens, hundreds, maybe thousands of jobs for Brazilians.

Besides, there is also a fundamental lesson in this for Bolsonaro and Brazil. A conservative customs agenda ensured Bolsonaro 15% to 20% of votes in the second round of the election. The remaining 35% to 40% of the votes he got were due to his firm discourse on combatting corruption and the modus operandi of Brazilian politics, aversion to the PT (Workers Party) and – to a lesser degree – due to his liberal economic stance.

Now in office, his nearly exclusive focus has been the conservative customs agenda and the combat against leftism. Combat against corruption was weakened by the approval of the so called package on the abuse of authority, left without any firm opposition from Bolsonaro. Besides, the nomination of his son to the Brazilian embassy in Washington will be used by his opponents to convince voters that Bolsonaro did not alter the way politics work in Brazil.

The economic agenda, on the other hand, has made great strides, especially with the Social Security Reform and the Provisional Measure on Economic Freedom. This progress, however, owes very little to Bolsonaro’s direct involvement, which never took place. This is where the danger lies.

There is still need for Congress approval of many other fundamental economic measures to allow Brazil to grow faster and generate more jobs and better salaries, beginning with the Tax Reform and an encompassing privatization program. The question is – how long and how much will the economic agenda continue to progress without Bolsonaro’s unconditional support grounded on his political capital? This question is fundamental because without advance in this agenda the future of Bolsonaro and of Brazil run the risk of being the same as Macri and Argentina. To put only part of the house in order may not be sufficient for the economy and the lives of most Brazilians to improve enough to guarantee his re-election and, above all, the continuity of a project of liberalization of the Brazilian economy. This risk is especially significant considering that a global recession is apt to occur before the end of his mandate, with major negative impacts on the Brazilian economy.

In short, Bolsonaro was elected for vehemently criticizing the corrupt Brazilian political environment. Besides his concrete contribution in this field, what will re-elect him or not will be the performance of the economy. A good performance requires the approval of several measures in Congress, which in turn may require a more significant commitment by Bolsonaro.

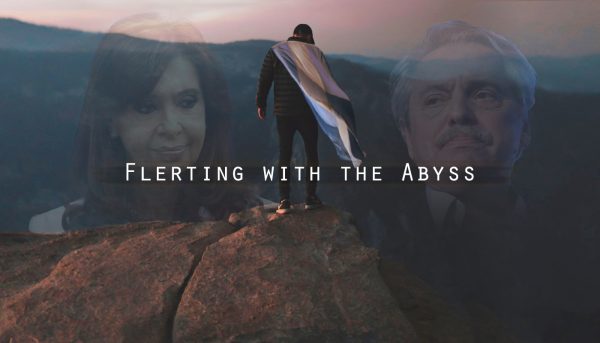

If he remains nearly exclusively focused on the conservative customs agenda, as he has done so far, and should it ensue that the economy falls short of the target, Bolsonaro and Brazil may have a destiny similar to that of Macri and Argentina, meaning a new flirt with the “petista” (Workers Party’s) abyss or that of Ciro Gomes’. Should it happen and Bolsonaro’s cherished conservative agenda will go down the drain – which does not bother me at all, on the contrary. However, along with that we shall lose the structural advances in the Brazilian economy that were so hard to achieve after Dilma Rousseff’s departure from power. In that case we Brazilians may end up sulking in yet another bitter economic crisis, like the one in the Dilma years, which was the longest and more acute the country experienced in at least 120 years. Brazil and Brazilians do not deserve that.

Ricardo Amorim is the author of the best-seller After the Storm, a host of Manhattan Connection at Globonews, the most influential economist in Brazil according to Forbes Magazine, the most influential Brazilian on LinkedIn, the only Brazilian among the best world lecturers at Speakers Corner and the winner of the “Most Admired in the Economy, Business and Finance Press”.

Click here and view Ricardo’s lectures.

Follow me on: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram e Medium.

Translation: Simone Montgomery Troula